The design advocate: A profile of Elodie Boyer

Commissioned by Pulp MagazineBrand consultants are not generally known for their fierce love of design. Designers sometimes ignore the briefings they have painstakingly put together, the process can be chaotic, and the outcome can defy rationalization. Elodie Boyer is the exception. She is deeply in love with design, and in turn loved by the designers she works with for her unrelenting advocacy of their work. She has earned the trust of her clients that design can deliver; clients who often take a leap of faith by hiring Boyer and her team to create unconventional work in conventional spaces. Such a reputation was not built overnight, but rather it is the outcome of a pursuit that has taken a lifetime.

Boyer grew up on design without being aware of it. “My parents were twenty in 1968, a generation that was all about graphic design power. The cars, the graphics, the wallpaper, the clothes… People were crazy, and happy, and daring, and bold, and simple, and joyful.” Design simply formed the backdrop of her childhood without her being very aware of it. Sitting in the backseat of her parent’s Renault, she would rank the design of petrol stations. Her favorite was Elf, with its simple typographic logo and bold colors.

In London, during the pursuit of her Masters Degree in Marketing, she interviewed industry legends like Wally Olins, and something clicked. “I loved these people, how they were dressed, their office, the furniture, their lifestyle, they laughed a lot while working hard, everything looked so beautiful… This is the world I wanted to belong to.” Boyer recalls thinking.

That wasn’t exactly in the cards just yet. “At my first job I was working in the pharmaceutical industry. My office looked so dull, everything was grey, brown, beige, nothing looked bright.” Even so, she found an opening for design to trickle in. As the communication manager for clinical trials, she found that the company’s promise to deliver a unified testing methodology across Europe was undermined by its haphazard design approach. “We were saying we would do consistent clinical trials, but we could not even do consistent business cards.” The dusting off and cleaning up of visual identity became a rewarding effort.

She moved on to brand consultancy Carré Noire in Paris, before striking out on her own in 2002. Five years later she moved to The Netherlands, a microcosm for the beauty that had eluded Boyer’s projects so far. It was there that she finally found the designers and producers that were on par with her vision of quality, and who remain her close collaborators to this day. “I had seen the PTT identity* exhibited at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, and I was fascinated by a country that would host an exhibition of brand guidelines. I knew that could never happen in France.” A year later, her MA mentor Nicholas Ind, introduced Boyer to Studio Dumbar.

She was brought in for the rebranding of French insurance company AG2R La Mondiale. The results would go on to set the example in France for how corporate brand identities could also be done. The experience was a turning point in her career. “There is a before and after this project. Before, we could get close to what I loved the most, but it was more by luck, whereas after Studio Dumbar, it was by default.”

[image: Thello, London bus. Caption: her work for the Thello train between France an Italy, and the Original Tour (iconic tour buses in London), take her signature style of branding to the streets.]

In 2010, she returned to France, bringing her Dutch design connections with her – albeit digitally. She settled in Le Havre, an unlikely choice, since the provincial town neither houses large corporates nor a blazing creative scene. But despite, or perhaps because of, this unexpected location choice, Boyer was able to bring the different elements of her passions together into a one-of-a-kind professional practice.

Her future revealed itself in the public spaces where her branding work lived, for which Boyer feels great responsibility. “Our hidden agenda is that the public cannot avoid our client. But our fight is trying to do so with grace, with humor, to make it joyful if possible, but always with respect to public space. This is our strength: maximal visibility with meaning inside.”

Her scrutiny of brands in public space lead to her documenting signage across the city. She took photos of hundreds of logos on shop windows and office facades, some unintentionally beautiful, some with badly spaced lettering, or with novel methods of installation. This obsession became the topic of the first book by her own independent publishing house: ÉDITIONS NON STANDARD. Another channel for design advocacy was born.

[image: cover lettres du havre.]

ÉDITIONS NON STANDARD is a client-free harbor to explore the combined pleasures of literature and design. The books offer the reader a tantalizing experience of all senses, where story, image, type, paper and weight come are all designed with equal consideration. The publishing house is a collaboration between Boyer and Jean Segui, a local author, who became her partner in life and work, designers like Patrick Doan and Rejane Dal Bello, as well as printer LenoirSchuring.

“To create is really scary, it is fear, it is vertigo. We all have to embrace this creative vertigo, but not the kind that comes from the question, ‘will this be validated’ by the client? The only thing we accept as a no [to a great design idea] is if it is technically not possible or way too expensive.” The outcome is a new type of literature that wins design awards.

One such book is Ligne B, a novel with 15 chapters, written and named after the 15 stops of the tram B in Le Havre. Each chapter is illustrated by photographs taken on the tram line and combined they tell the stories of local characters.

[image:ligne B]

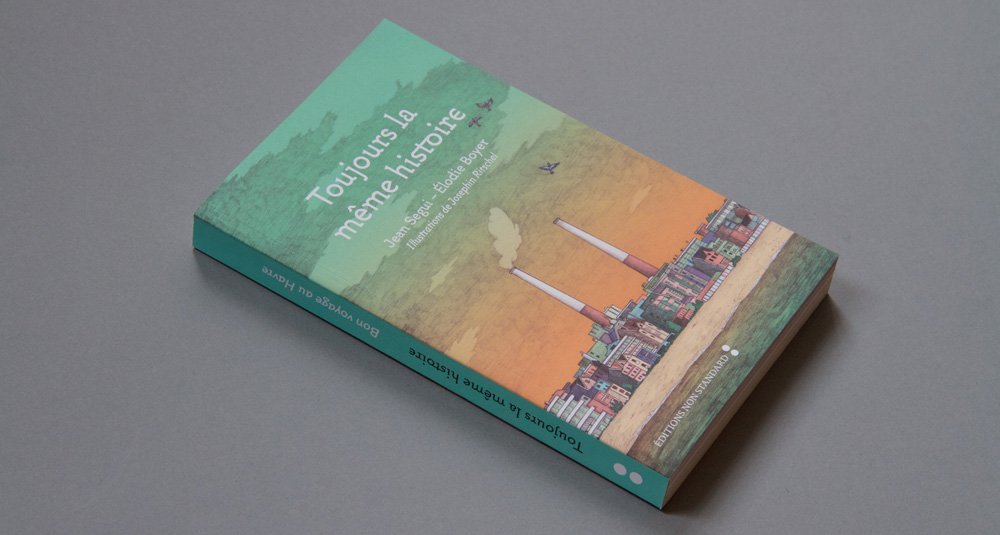

Toujours La Meme Histoire, published in 2017, revolves around a man who lives in fear of newcomers, told in three versions of increasing length and complexity in one book that is suitable for children, teenagers and adults. The evolution of the story is enchanced by the changes in design of Patrick Doan and the illustrations by Josephin Ritschel for each of the three parts.

[image: toujours la meme histoire spread]

Though Boyers design advocacy entered Le Havre through its bookshelves, it did not stop there. In 2016, she teamed up with Pierre-Yves Cachard, director of the University Library of Le Havre, to develop a project on the city’s beach. They realised the iconic white cabins lining the shore were the ideal canvas for a design intervention. They invited Dutch designer Karl Martens, who subsequently designed colorful stripe patterns that turn a rather unremarkable beach into a feast for the eyes.

[image: beach shacks by Karel Martens]

If Boyer’s job sounds like a dream, the reality of it is quite different. “I think we are like the Rolls Royce of corporate identity. Everything we do is like jewelry, it is amazingly customized and we spend lots of time to find these solutions, and we struggle, we really struggle. It looks simple and natural, but it takes so much time to get there. Like when we made the busses for Paris and London. Once it is all sorted out, it looks so simple, like there could only ever have been one bus. But we started with over one hundred designs and there were so many conversations, and choices, and doubts.”

Over time, the world has come to love the type of design that Boyer has always advocated. “In 2007 we were fighting against 3d effects and shadows, but now the trend is more aligned with what we have always done and what we will always do. So now we don’t have to fight so much.” She is aware that the tide will change again one day. “Whatever the trend, we will use this style for all our lives. Bold, simple, bright.” Voilà.

* corporate identity of the PTT (Royal Dutch Telecom), designed by Studio Dumbar in the nineteen eighties and nineties, and documented in elaborately designed identity manuals produced with special printing techniques.